Post by Chloe Tremper, Science and Education Intern 2014

Throughout this past summer, I have gotten to know the forests of Hurricane very well, particularly the spruce-fir stand on the northern half of the island along Slocum’s Trail. Red spruce (Picea rubens) is by far the most dominant species on the island but is generally only found in the interior the spruce-fir stand on the island. White spruce (Picea glauca) lines the edges of the stand along trails and the coast but is completely absent from the interior of the stand. This reflects the white spruces near inability to survive in suppressed conditions and reproduce in closed canopy conditions. Balsam fir (Abies balsamea) is the last species of tree I found within my study area and the least abundant. However, when it was found it was generally in plots near the coast and it was always found in concentrated groups.

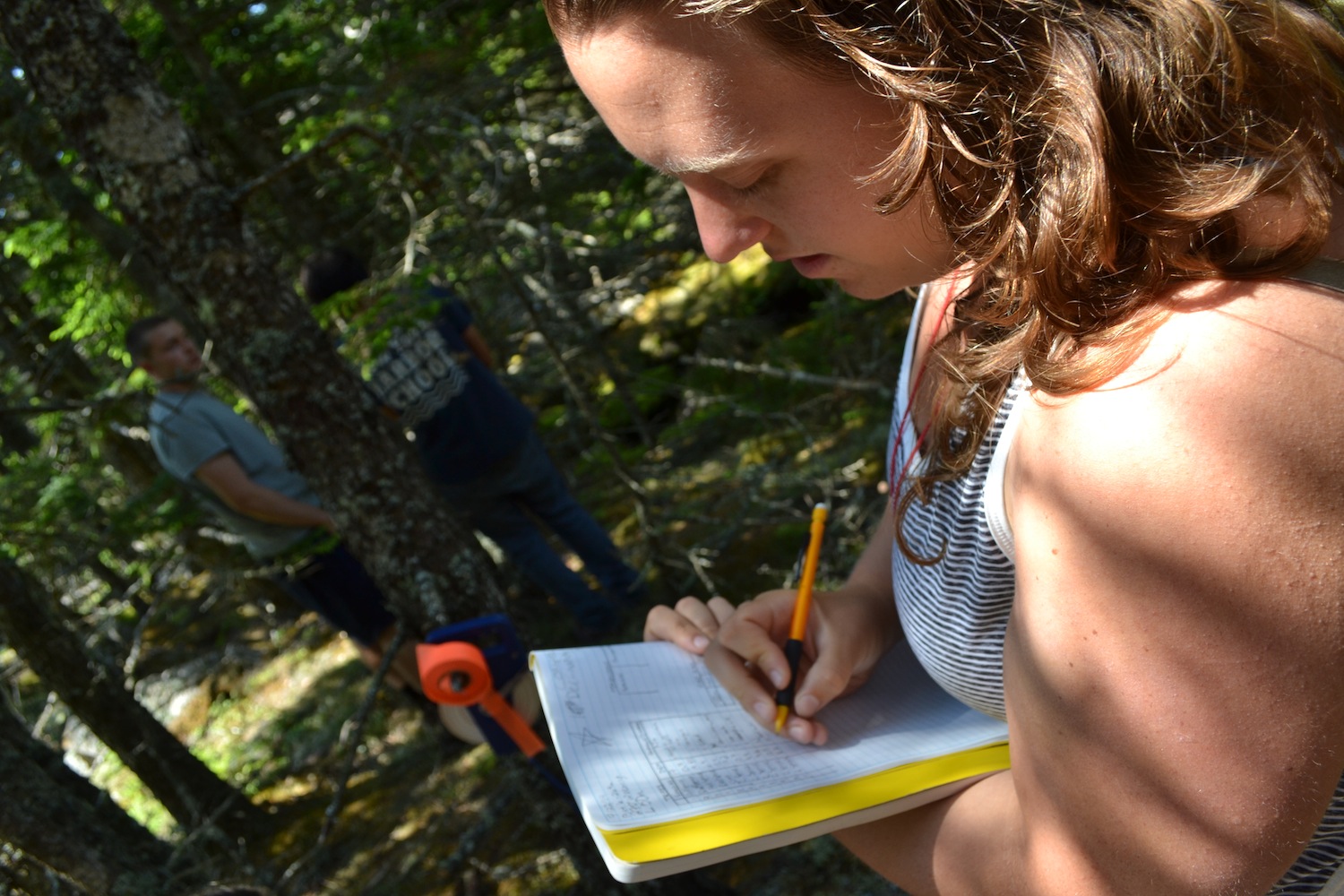

Coring a red spruce to count growth rings to estimate age

Very few of the trees within my sampling area had reached their full growth potential, despite some of them being well over one hundred years old. This can mostly be attributed to having grown in a less than favorable environment with high competition for very limited resources among individual trees. Hurricane’s climate (particularly its regular inundation of ocean fog) and shallow, acidic soils are two factors making the island a harsh environment for the trees to survive in.

Overall, Hurricane’s spruce-fir stand is doing pretty well. Fire is the biggest risk currently facing Hurricane’s forest due to the massive amount of dead woody debris on the forest floor and the fact that spruce needles are extremely flammable. The possibility of windthrow (when trees are uprooted by wind) is also fairly high due to the shallow soils and the naturally shallow rooting systems of spruce and fir trees. There is also the potential for an infestation of witches’ broom (a dense mass of shoots growing from a single point off a tree caused by variety of things – generally fungi or a virus) as it is already present on some of the spruce trees along the eastern coast of the island.