Post by Ben Lemmond, UVM Field Naturalist

Just for a moment, rewind your mental tape back late March of of this year: that time when everybody starts talking about spring (because, you know, the equinox and all) but, if you live in New England, the actual idea of anything turning green anytime soon seems pretty far-fetched. It’s that magical time of year when the petrified dog poop and cigarette butts of last Fall start to emerge from underneath the ash-colored snow on city sidewalks, not to be covered up by anything green for another two months. Poet and author Ranier Maria Rilke once said “The future enters into us, in order to transform itself in us, long before it happens.” Think back to early spring. Even in that grey season, with the gears of spring still stuck in neutral, what big moments were setting the stage so that they unfold as soon as things warmed up?

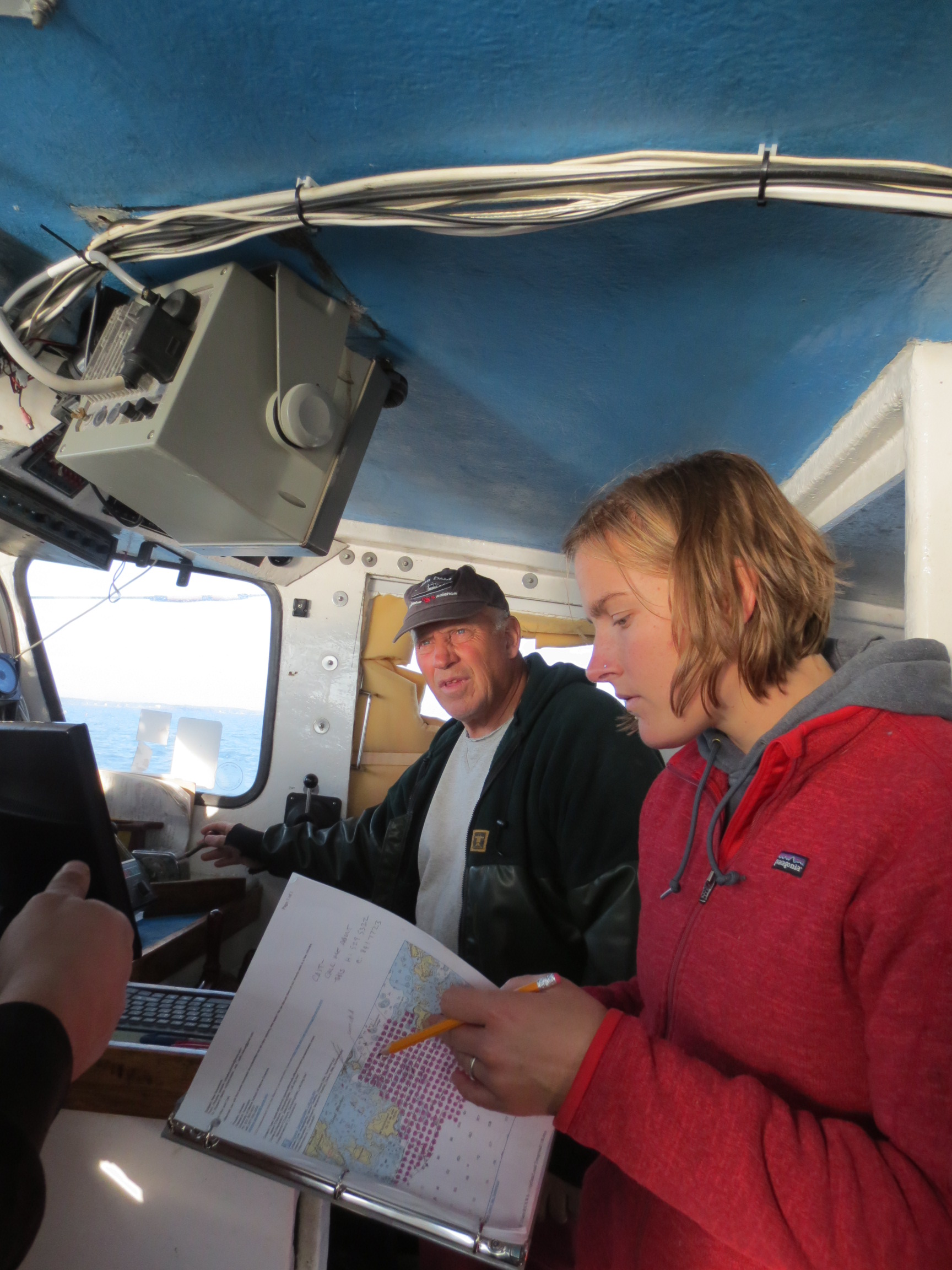

It was around this time of year when I found out that I would be working with the Hurricane Island Foundation for my master’s project, though I hadn’t a clue what exactly that would mean. Being a graduate student, I’ve learned, means constantly doing things you feel wildly unprepared to do. It’s a special kind of limbo, one where you’re constantly travelling between paradoxical versions of yourself: student and teacher, professional and newbie, expert and idiot savant. This way of life almost guarantees surprises, since everything moves too quickly for any part of it to become familiar. Suddenly I am standing in front of a lab room full of college sophomores, explaining how to pipette solutions through a channel slide with a thin slice of rabbit psoas muscle mounted on it, in the hopes of making it twitch with the right combination of solutions. In what strange spring was that vision of myself planted?

Field fashion

I’ve now been on Hurricane for four full weeks, conducting an initial ecological survey and developing my own coarse-filter map of general landscape and vegetation patterns here. This means that I’ve been spending most of my time wandering through the island with a canvas bag full of nature-nerd paraphernalia: field guides, a GPS, binoculars, a hand lens, plants to be pressed, many of these items (except the plants) cycling through my free hands and pockets or slung around my neck, depending on the terrain and the amount of backup I needed to make my way knowledgeably through it. I have to admit, this task has been more challenging than I expected, mostly because the better I feel I understand the plant communities here, the more fragmented, temporary, and in transition they appear to me.

The flip side of this apparent chaos is that every day in the field is another opportunity to be surprised. The other day, I found the island’s one and only eastern white pine next to the island’s one and only red maple on a hillside of an obscure outwash I decided to explore on a whim, after my field foray was officially over for the day. White pines and hardwoods certainly used to be a presence on Maine islands, but were almost entirely cleared for shipbuilding or lumber by the mid-1800s. On a 125-acre island where many of the spruce are ageing out, the presence of these two species is significant, even though I don’t know exactly what to make of it yet.

An interesting facet of the island is that, species-wise, there are many of these lone individuals here: in addition to the pine and the maple, there is exactly one American elm, one grey willow, one royal fern, and one steeplebush here – at least that I’ve found after four weeks of walk-throughs. The other week, a bird-banding class caught the first robin and red-eyed vireo that any of us had seen on the island. Anywhere else, many of these species would be completely unremarkable. But on this island where things are moving constantly and complexly, a place where chance encounters often teach me more than what I set out to look for, even a robin or a pine tree regains some of the magic of something seen for the first time. I know that sounds hokey, but it’s true: I have never been so excited to see a pine tree. That might not be what I write in my official report at the end of it all, but for now, I’m really enjoying the way that being on a small island brings these small surprises in to sharp focus.

Ben Lemmond is a graduate student in the Field Naturalist program at the University of Vermont. Learn more about the program at: http://www.uvm.edu/~fntrlst/

Looking out from the high cliffs