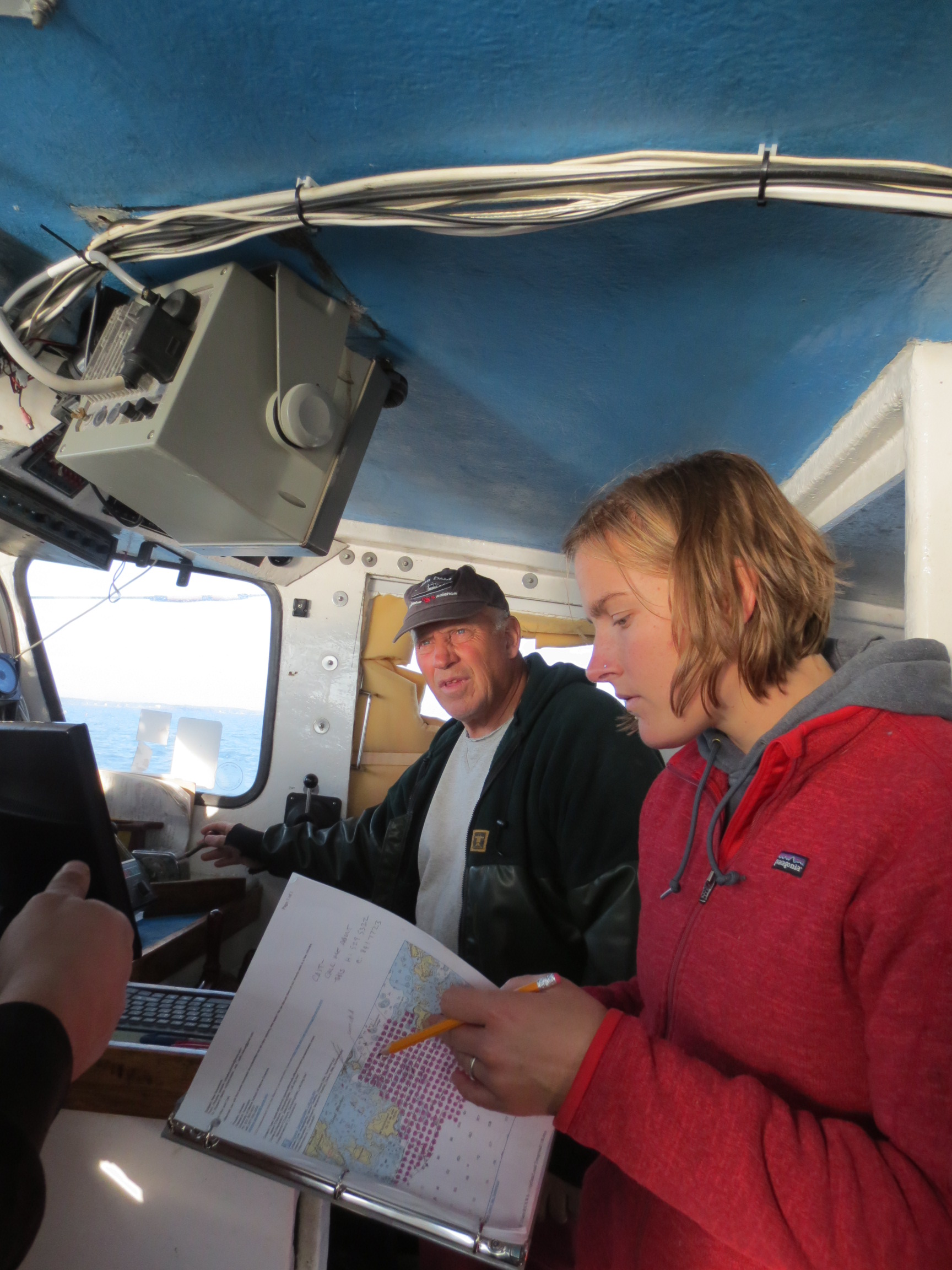

So these processes lower ocean pH...what's the big deal? And which processes are having the biggest impact? We don't know all of these answers yet, but Dr. Salisbury and other scientists are documenting the seasonality of CO2 and pH levels in the surface ocean to see how much phytoplankton blooms, freshwater runoff, upwelling, and horizontal mixing are contributing to changes in pH compared to atmospheric CO2 emissions. We do know that lower pH impacts a lot of organisms in the ocean that we commercially harvest. Lower pH drops the concentration of carbonate ions in the ocean which is an important part of the compound calcium carbonate--a crucial ingredient in creating the shells of commercial shellfish including lobsters, oysters, scallops, and clams. According to Joe Salisbury, shellfish aren't the only critters that may be impacted. Fish can also face reproductive and olfactory (sense of smell) stress in lower pH environments, and low pH can even change how sound travels through water, which may impact how whales and other marine mammals communicate using vocalizations underwater.

As an oyster farmer, Bill Mook has seen first-hand what lower ocean pH can do to his larval oysters. Larval shellfish are much more vulnerable to ocean acidification compared to their adult companions. According to Mook, the calcium carbonate form that larvae use in their shells is aragonite, which is much more soluble (easily dissolved) in lower pH conditions. Larval oysters typically develop from fertilized eggs in 24 hours and live as swimming larvae from 14-16 days. Mook has noticed that since 2006, there have been more incidents at the hatchery where fertilized eggs do not convert to larvae and just die, or the larvae grow much more slowly, stop feeding, and generally take longer to go through metamorphosis. These events are often linked to runoff events from rain storms, and may be the canary in the coal mine for what the future may look like for shellfish.

So what is Maine and the scientific community doing about it ocean acidification? Damian Brady of Darling Marine Center, UMaine, and Esperanza Stancioff of University of Maine Cooperative Extension are great examples of other researchers and educators that are trying to learn more and educate people about the problem. Damian Brady works with numerical models to try to learn more about how changes in temperature, precipitation events, runoff, and land-use practices can mitigate some of the conditions we are seeing in the ocean. The state of Maine has also been one of the first states to mobilize forums, conferences, and meetings focused on ocean acidification, and there are several formalized networks and organizations that are also working to learn more about ocean acidification. Two that were mentioned during Coastal Conversations are The Northeast Coastal Acidification Network (NECAN) and The Ocean Acidification Commission (OAC). NECAN has been working to compile data and research around ocean acidification including hosting a series of webinars and a 2-day "state of the science" workshop. The OAC was formed less than a year ago by the Maine legislature to compile information about existing and potential impacts of ocean acidification on commercial species. Their goals involved identifying existing research and potential monitoring, mitigation, and education opportunities to continue to engage researchers, industry members, and the public in this issue. The OAC recently released a report (a link to the draft is here) outlining the following recommendations:

- Increase Maine's capacity to monitor the impacts of ocean acidification

- Reduce CO2 emissions in Maine, and encourage new innovative technology to help make these reductions possible

- Reduce nutrient and freshwater runoff

- Mitigate, remediate, and adapt (for example, preserve macro algae (seaweed) areas, and use shells to buffer mudflats)

- Educate the public about this issue

- Sustain these research and mitigation efforts in Maine in the form an ocean acidification council to see this process into the future

If ocean acidification is a topic that interests you as a student, researcher, or citizen, then get involved! There are many research questions yet to be asked and explored, and opportunities to help Maine move forward to mitigate our impact on our oceans. The state of Maine currently doesn't require schedule maintenance of homeowner septic systems, there is not yet a citizen science ocean acidification monitoring network, the body of published scientific literature on ocean acidification is less than 10 years old, and there are still opportunities to develop curriculum around ocean acidification and share what you know with others! The time is now and you can make a difference!

At the very least, be sure to stay informed by reading up on marine conservation issues and by tuning in every 4th Friday of the month to Coastal Conversations on WERU 89.9 FM or live-stream from weru.org.