Post by Scallop Research Intern, Bailey Moritz

Branwen (left) and Cait (right) get ready to plunge into the cold Acadia waters in search of coralline algae.

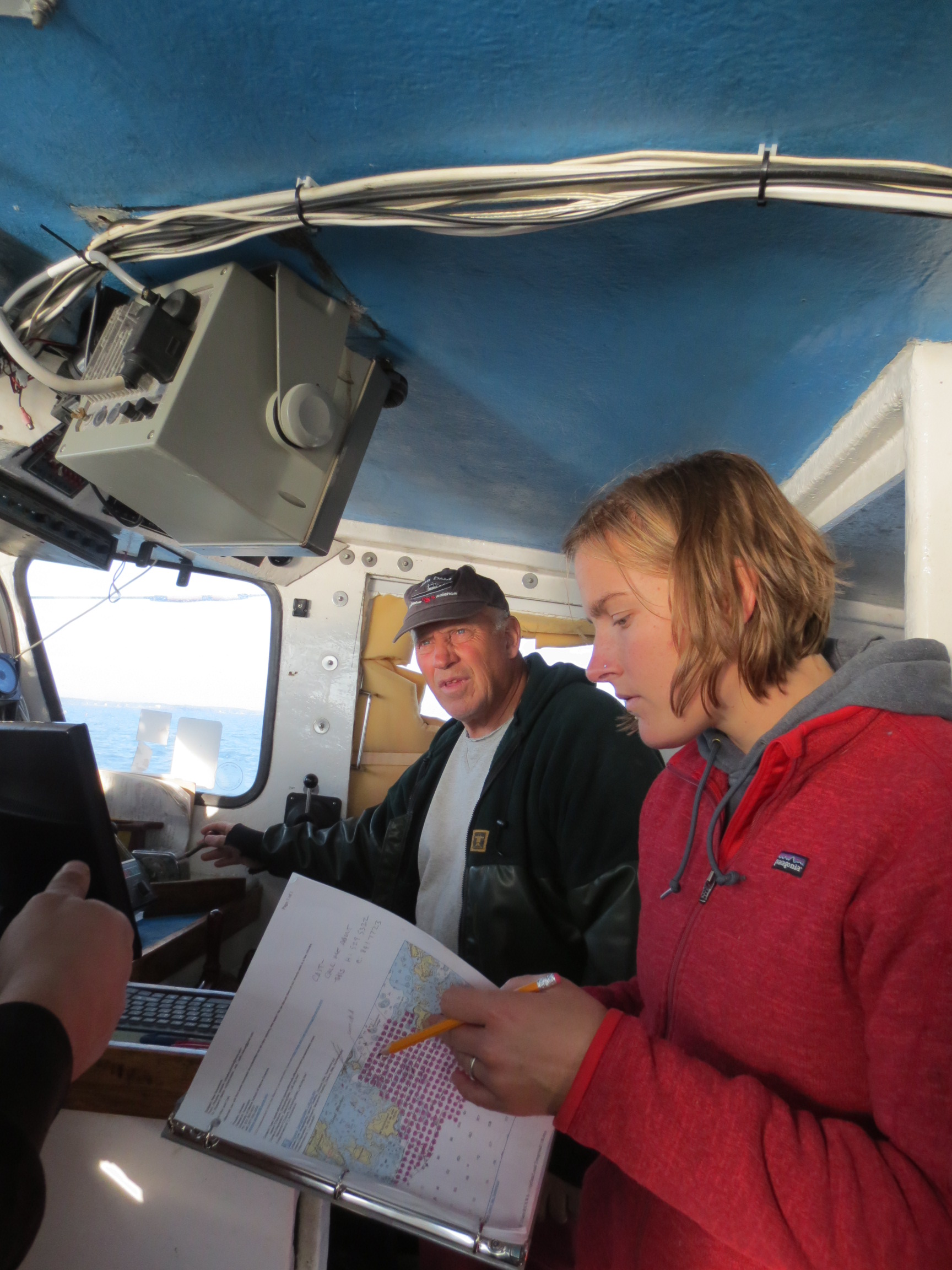

Collaboration in science is really useful for carrying out successful research. Maybe you don’t live in the same place as what you are studying. This is the case for Dr. Branwen Williams, a researcher and professor for the Claremont Colleges in California, who is investigating coralline algae from its southern limit in Maine all the way up to the Arctic. Cait has collected samples for the past couple summers to send back to Branwen, but this year she made the cross-country trek to dive for the algae in Acadia National Park herself. The Schoodic Institute was generous enough to host us while we carried out a total of 5 dives to first find the algae, deploy a temperature probe at depth to monitor the algaes growing environment, and collect about 140 coralline samples to be shipped live back to the lab.

Field work can require a lot of gear and talent to pack it all in.

A “modern paleo oceanographer using marine organisms as tools to look at environmental change,” Branwen is interested in the calcium carbonate skeleton of the domed, deep-pink algae that can be used as a proxy for reconstructing past climate. Tropical corals are commonly used to understand how climate has changed in equatorial regions, but less is known about paleo climate in the mid to north Atlantic region, an area particularly susceptible to modern climate change. Depending on the water temperature, the algae will substitute Mg for Ca when building its carbonate skeleton. The Mg/Ca ratio serves as a proxy for the temperature of the ocean when the algae were growing. Similarly, analyzing boron isotopes provide insight into past pH conditions. The coralline algae can be 100’s of years old and Branwen hopes to reconstruct a record of ocean conditions back to the 1700’s.

Coralline algae, which form a crust-like cover over anything from rocks to mussel shells, may be threatened by warming waters as they grow best in the colder climes. This could take an ecological toll, as they are substantial habitat builders in more northern latitudes. We’re excited to hear what Branwen and her colleagues discover from these little corallines! The more we understand about how climate change is impacting marine creatures, the better we can prepare ourselves and our local environment.