Microcredentials on Hurricane:

Training for Maine’s Marine Economy Future

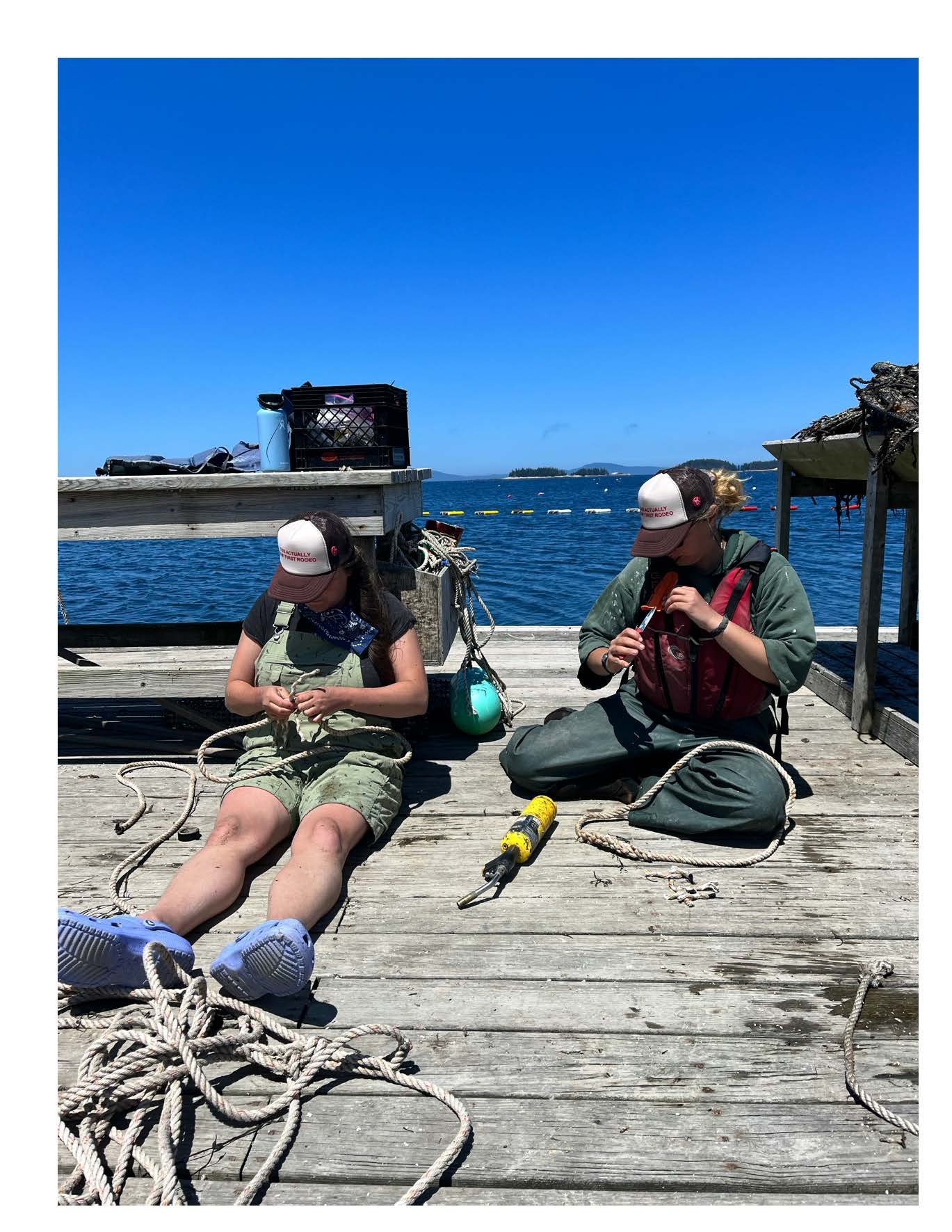

Chloe Finger is a bonafide marine engineer. Borrowing from her growing up on the schooner J&E Riggin and her expertise from working last year on Hurricane Island’s Facilities team, this week she completed an oyster grader on island to efficiently sort the oysters that we grow on the Hurricane Island aquaculture farm. She’ll begin using this tool with Micah Conkling, her fellow Aquaculture Farm Assistant this season who brought oyster-farming and aquaculture-development research experience to the farm, but only after he finishes removing the encrusting organisms that foul the nets that we use to grow our scallops.

While Chloe and Micah’s tasks this season varied weekly—from boat handling to animal husbandry to SCUBA diving on our farm’s moorings—their duties for the season overlapped with the hands-on aquaculture curricula that we designed with the Hurricane Island Education team for this year’s two cohorts of high-school aquaculture workshop participants. In all, the skill-building Micah, Chloe, and our aquaculture students experienced is part of innovative occupational-development programming in vocational education: namely, that of “microcredentials.”

Microcredentials are certifications of proficiency awarded once a learner of any kind completes a training that an established institution recognizes as sufficiently rigorous. In our case, Hurricane Island has been building a curricular pathway with UMaine’s Center for Cooperative Aquaculture Research (CCAR) and Aquaculture Research Institute (ARI) and other partners to teach the basics of saltwater aquaculture such that Chloe, Micah, or our high-school students may receive official, résumé-ready certifications of their skills without needing to enroll in a traditional school. As a college student completes credit hours in a classroom to show they know their stuff, so can a student learning maritime skills outside the classroom, as long as an education authority approves their learning path.

While they also award official certifications, microcredentialing programs are often much shorter than conventional college courses (weeks instead of months) because they are aimed at making skill-certification more broadly attainable. Says CCAR’s Melissa Malmsteadt, “microcredentials are kind of brilliant—you can get a baseline level of interest in a topic to see if it interests you without needing to commit to a four-year college.” Microcredentials differ for youth and adult learners, and microcredential development accelerated during the COVID-19 pandemic as educators foresaw future impediments for traditional learning systems. However, professionalization programs for marine aquaculture are especially new because ocean-farming industries are still maturing in Maine and nation-wide (shout-out to the Gulf of Maine Research Institute’s 2020 strategy report on aquaculture workforce development in the state).

Thus are Hurricane Island’s adult and high-school aquaculture microcredentials still pilot programs while Chloe and Micah provide feedback on their skill-development, and as we field-test lesson plans to guide youth students through at least the first of three levels of ocean-farming proficiency. This season, however, we are proud that our youth participants completed Level 2 of UMaine’s youth Aquaculture Microcredential through our workshops; these students are on their way to receiving the first stage of UMaine’s adult Aquaculture Microcredential.

We are thoroughly excited to continue to integrate our marine research with Hurricane Island’s education initiatives. In the meanwhile, Chloe will fix the bilge pump on the skiff, and Micah will keep monitoring the saltwater aquarium he built to develop sugar kelp spores. Fortunately, they are comfortably accustomed to the range of competencies required for marine work.