Guest blog post by Science Educator Dana Colihan

Middle school marine biology striking their poses!

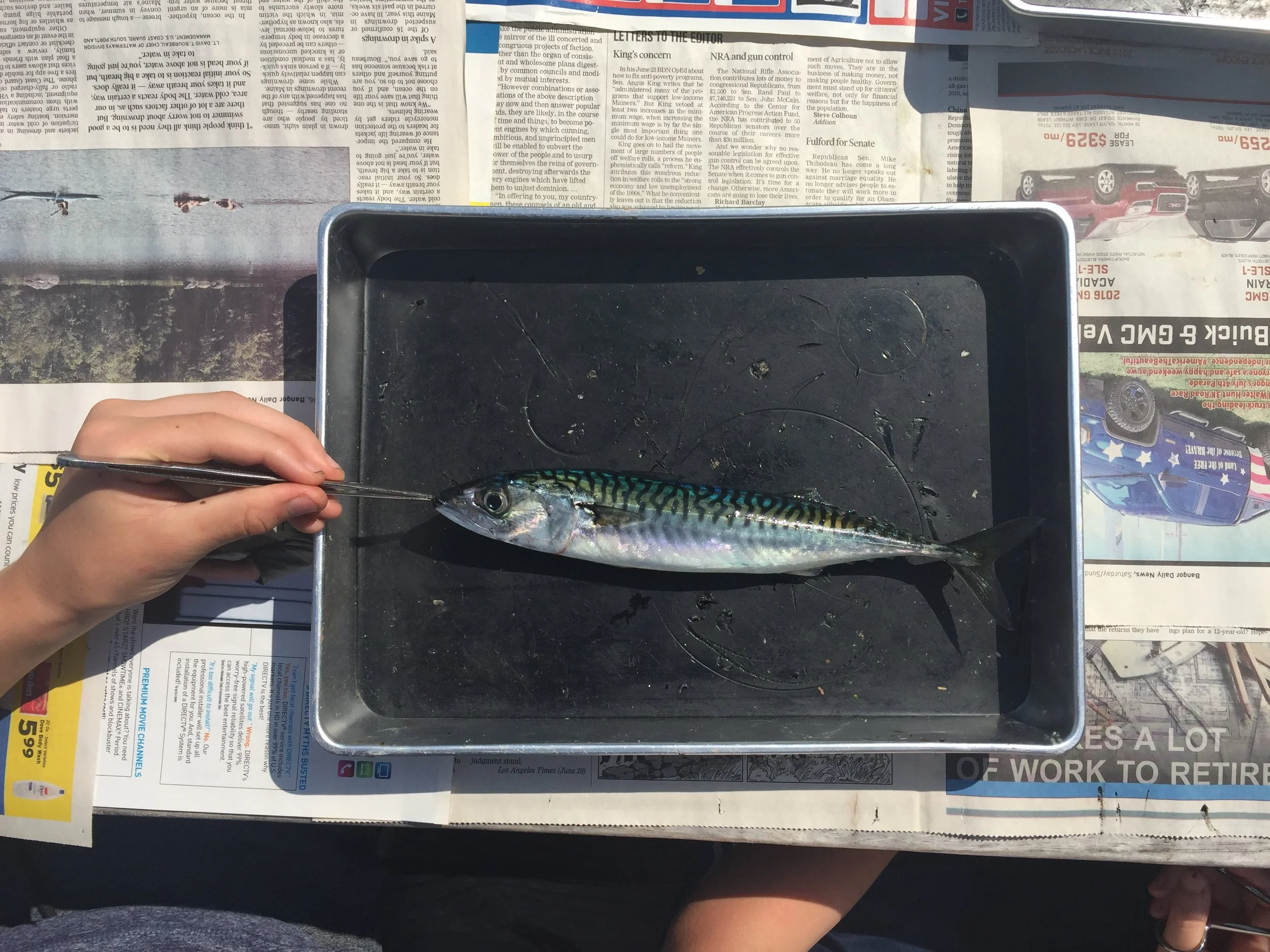

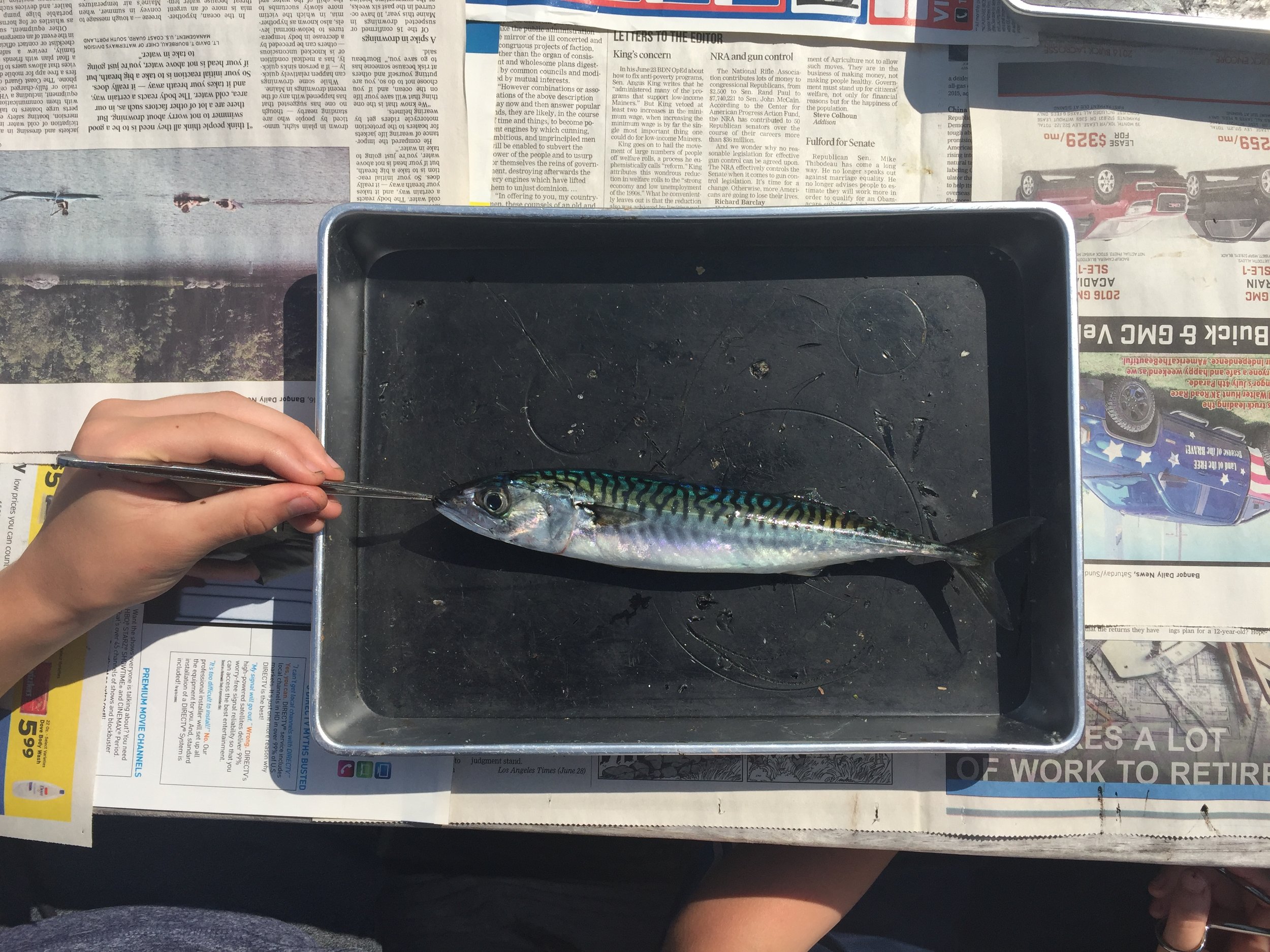

Examining the mackerel

Last week Middle School Marine Biology was fortunate enough to catch SIX mackerel while fishing with Oakley on Fifth Generation. Mackerel are a migratory schooling fish which reach the coasts of Maine in the summer. They are beloved by many a Mainer, and well known for their iridescent skin and dark patterns on their backs. These patterns are schooling marks, which can help a fish know to adjust their speed and align themselves with the rest of the group by looking at the marks of their neighbors.

Two years ago, I worked as Coral Reef Ecology Intern at the Cape Eleuthera Institute. A major aspect of my job was filleting and dissecting Lionfish to collect data on their stomach contents. While I had never dissected a fish before that summer, I quickly became extremely familiar with the ins and outs of dead fish. This is a skill I have brought with me to Hurricane Island and I have enjoyed sharing with different Hurricane Island programs. If you dissect a fish for someone else, then they have seen a fish dissection. But if you teach someone how to dissect a fish they can dissect fish for life!

Dissection discussion

Before breaking out the scalpels, Middle School Marine Biology had a conversation about what it means to dissect a fish. Why would we want to dissect a fish in the first place? What can we learn from it? Students went around, bouncing their ideas off each other. One student answered, “Through dissecting a fish we can see what’s inside of it!” Another responded, “If we look in it’s stomach, we can see what it’s been eating or if there are microplastics inside.” This is true! Dissections can be a really important way to learn about a species through observations and data collection. You can collect data through measuring its size, looking at a fish’s stomach contents to learn about its diet, and even find out its reproductive development through looking at a fish’s gonad stage.

Mack-daddy!

Through our dissections Middle School Marine Biology and I learned two things about Mackerel. Firstly, they don’t have swim bladders. Swim bladders are internal organ in bony fish that help them control their buoyancy, allowing them to stay in place without having to swim. If they are not punctured when captured, swim bladders can look like little bubbles filled with air in a dissection. Mackerel are some of the few bony fish that do not have swim bladders. They swim so fast and frequently that Mackerel do not need to float in the same way other bony fish do.

The second thing we discovered in our dissection was what looked like two centimeter snippets of hair wriggling in the guts of the fish. Our mackerel were infected with “herring worm” or Anisakis, a parasitic nematode whose larvae are eaten by crustaceans. These crustaceans are eaten by fish like Herring and Mackerel, in which Anisakis encysts in the fish’s gut before being ingested by marine mammals where they develop into adult worms. For Middle School Marine Biology, the herring worms were a particularly disgusting and fascinating part of the dissection.

Hannah and Serafin making the first inscision

Fish dissections are gross. They are messy and stinky. Your fingers get covered in fish blood and guts, and the smell will remain on your hands even after washing them multiple times. But I love that fish dissections are gross. I love the excitement students’ have sticking their fingers down a fish’s mouth to find it’s stomach. I love how much information you can learn about a fish from looking at its insides. Dissections are extremely educational, extremely hands on, and extremely engaging. My hope is that Middle School Marine Biology left Hurricane Island not only a little fisher than when they arrived, but also that someday in the future, they could teach someone else how to dissect a fish.