Young Artists on Display at Rocky City Cafe Express their Scientific Observations through Creativity Amidst a Changing Environment

Hurricane Island Center for Science and Leadership Partners with Center for Maine Contemporary Art and Rock City Cafe

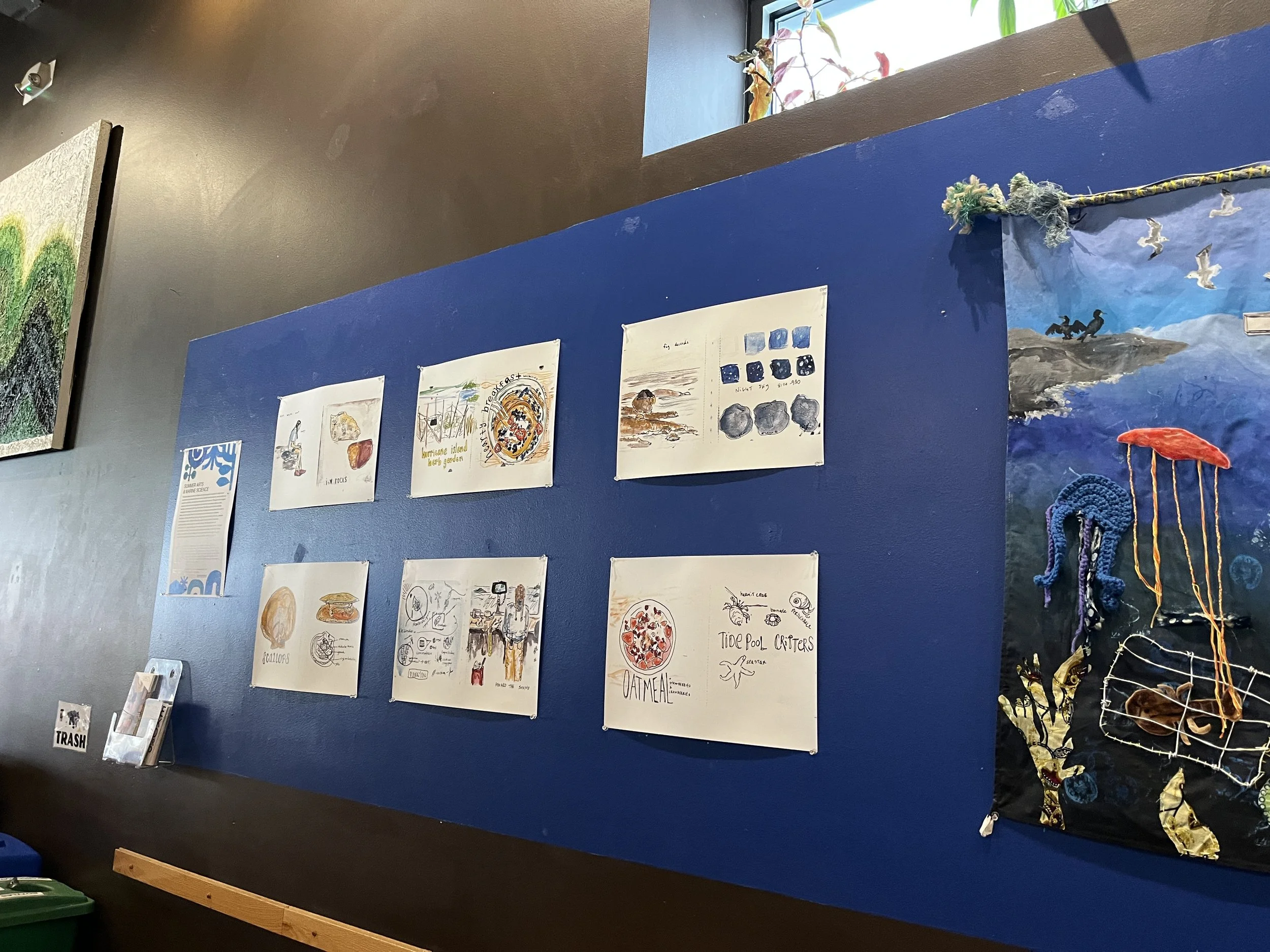

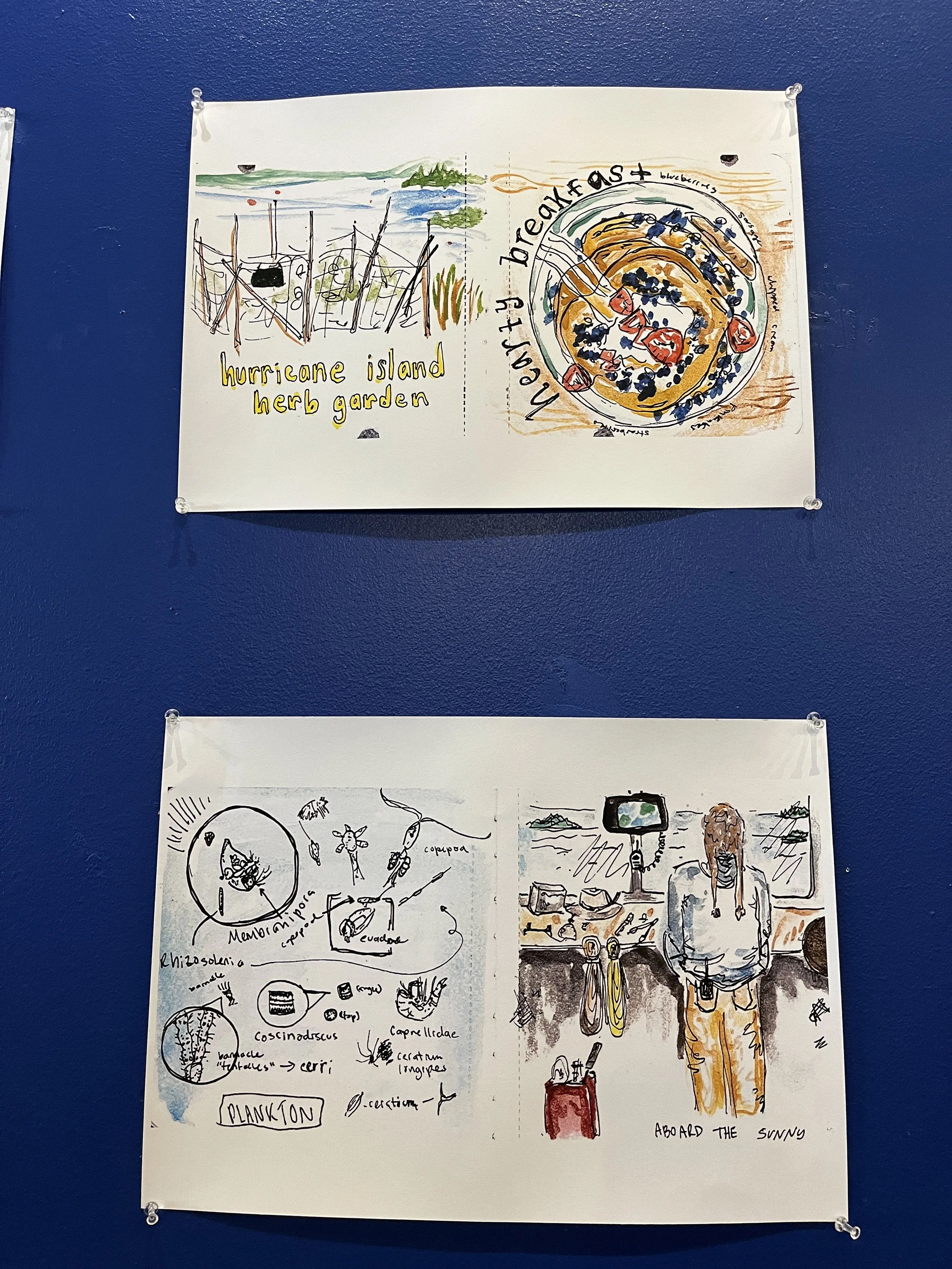

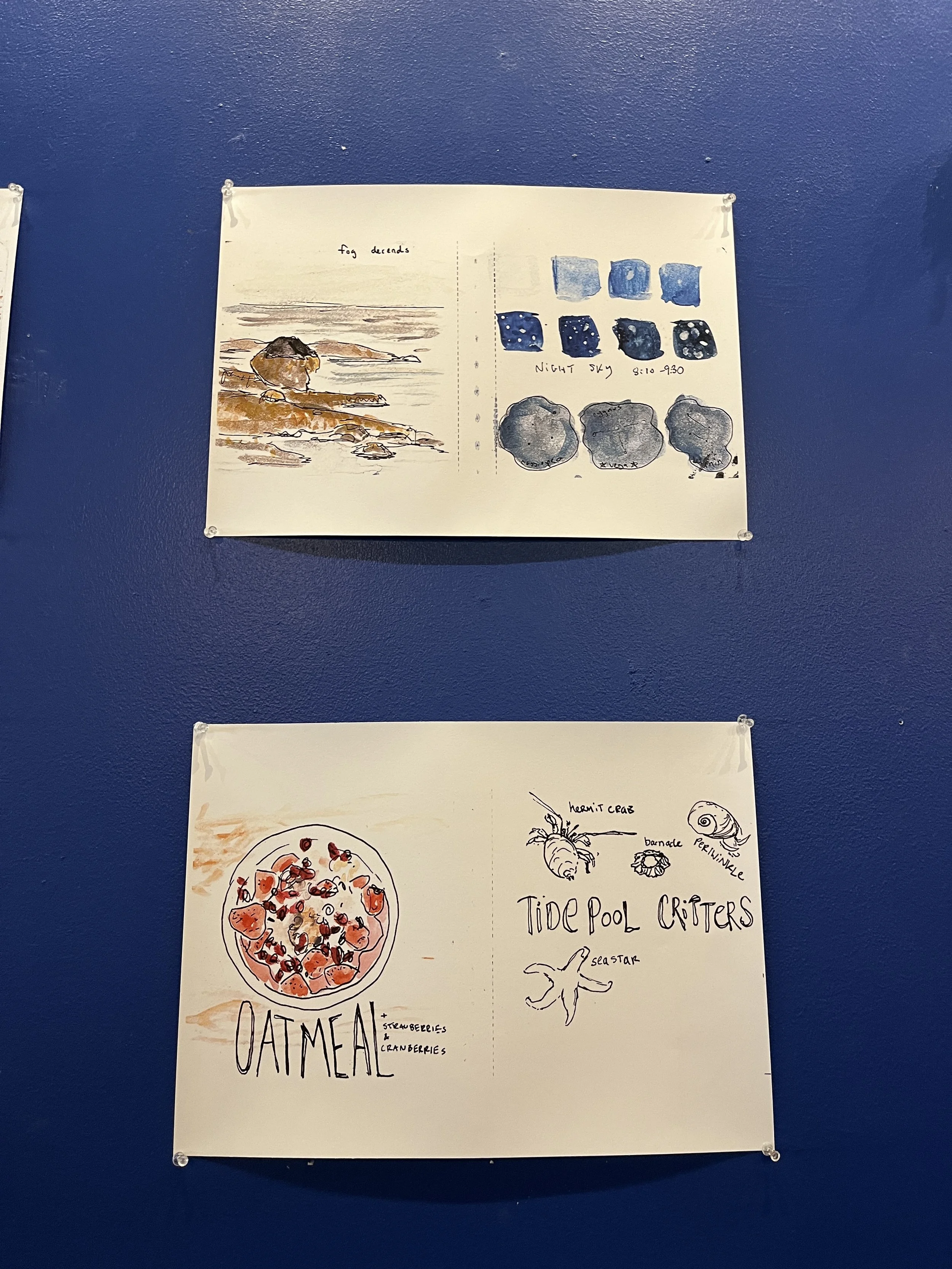

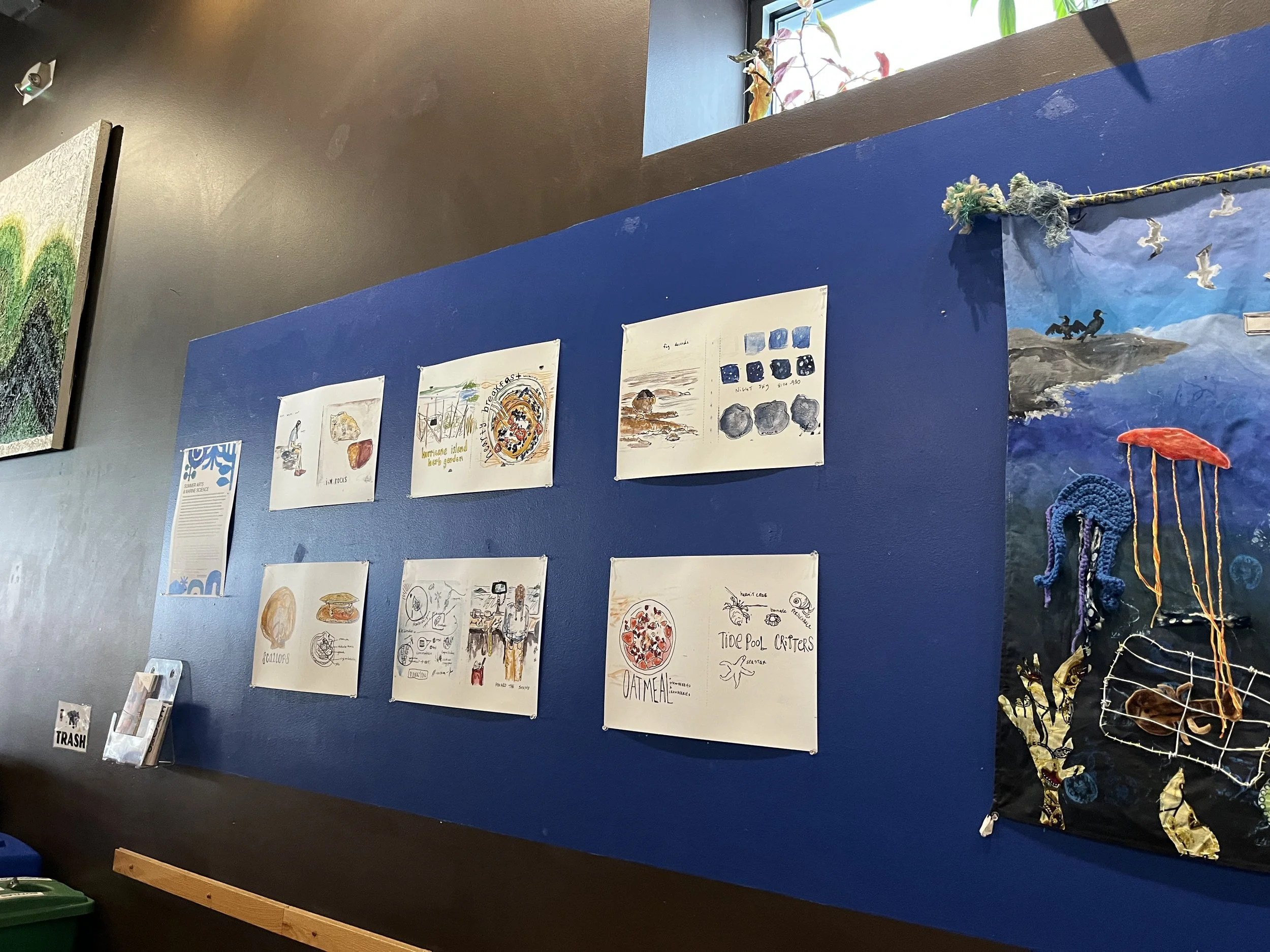

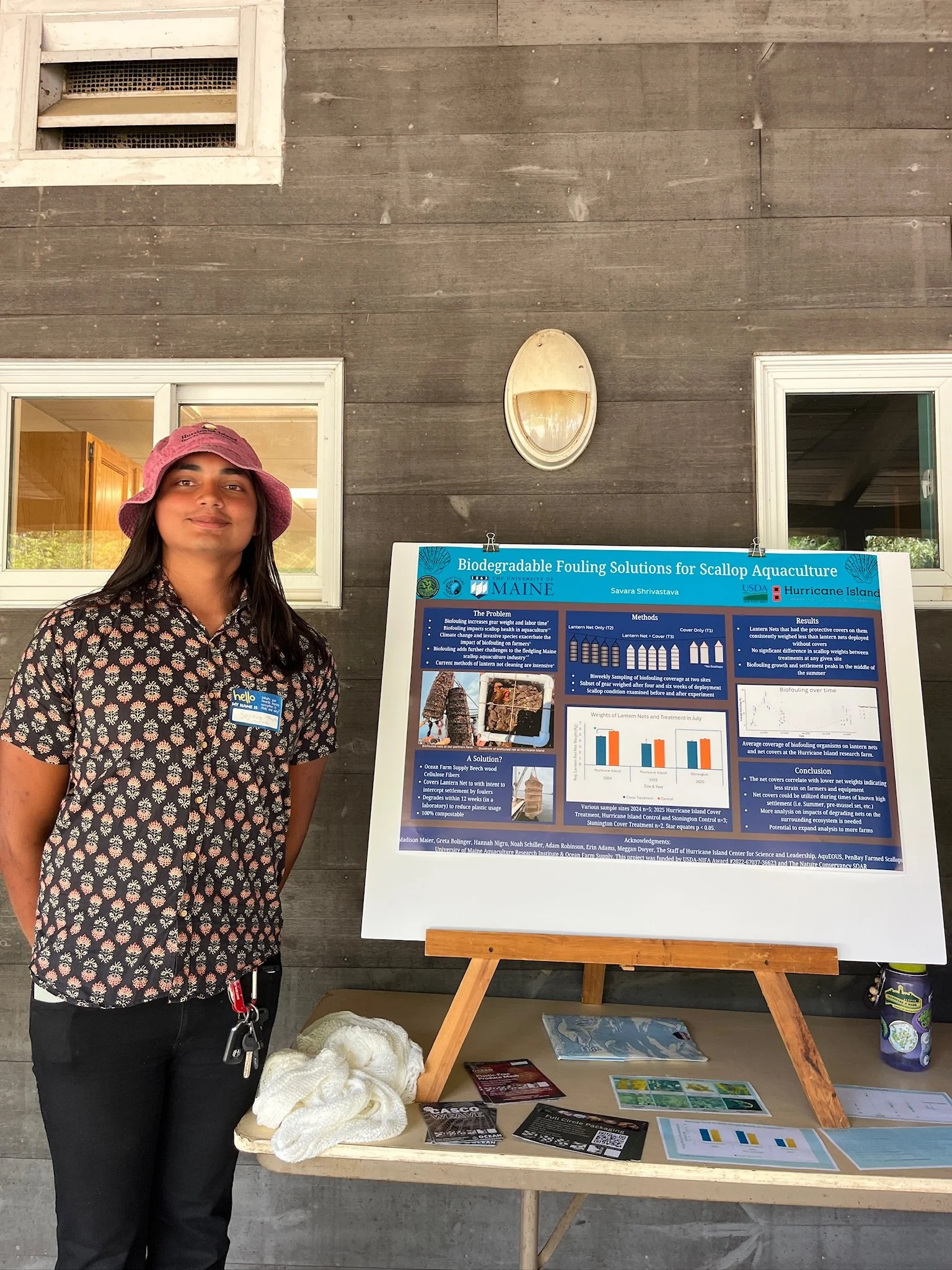

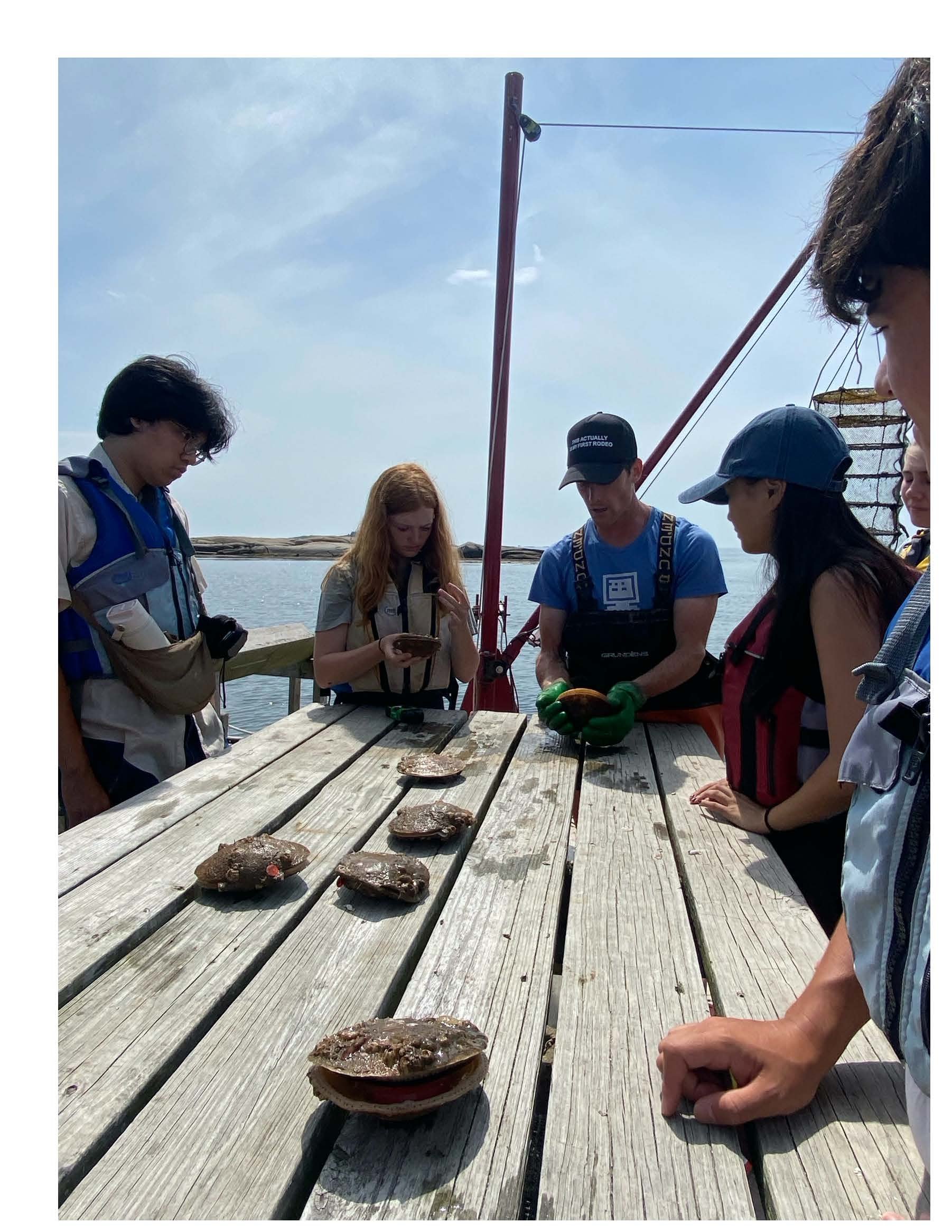

Hurricane Island Center for Science and Leadership recently ran an Art and Marine Science program for high school students on Hurricane Island. This summer program is designed for students who are passionate about ocean ecosystems and interested in gaining skills and practice in scientific communication through the use of visual art. Throughout the week, student participants dove into marine ecosystems and honed their observational skills to create beautiful, communicative, and impactful artwork. They explored the invertebrates inhabiting the seaweed covered intertidal zone on Hurricane Island, the planktonic communities of the Gulf of Maine, and took a deep dive into the recreational and commercial uses of marine resources, including lobstering and the growing aquaculture industry. In collaboration with Center for Maine Contemporary Art (CMCA) and Rock City Cafe this year, the students artwork is displayed for public viewing in Rock City Cafe in Rockland.

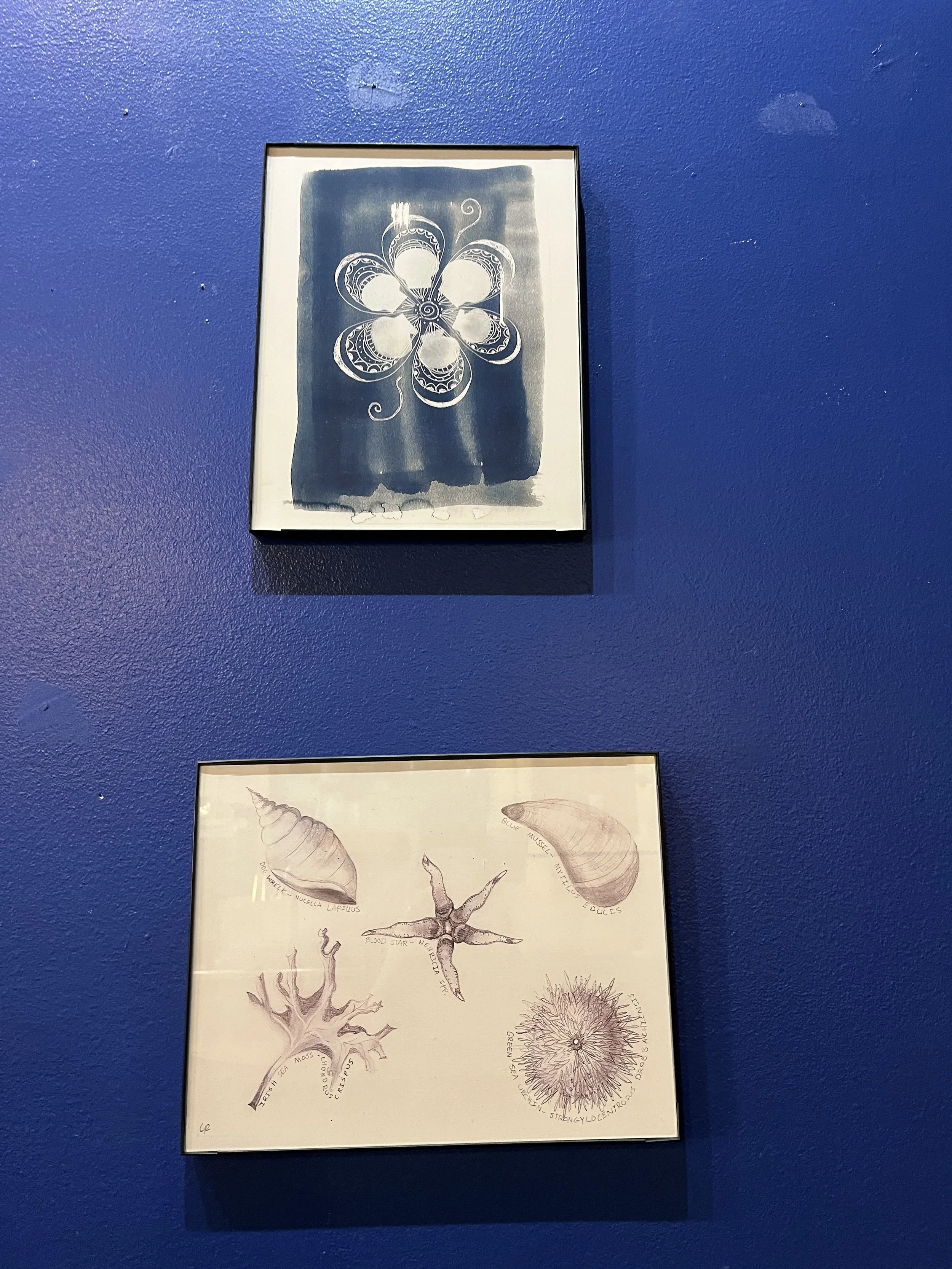

Each year, students in the Hurricane Island Art and Marine Science program create multiple individual art pieces including scientific illustrations, cyanotype prints, scallop structures, and many others. The students also work collaboratively to create one large piece of art to portray a certain ocean issue or topic. The art focuses on the growing aquaculture industry in Maine (specifically scallop aquaculture, one of the focuses of Hurricane Island’s research) and how it relates and interacts with vital fisheries, highlighting the potential for industry diversification to support more resilient coastal communities.

Center for Maine Contemporary Art is dedicated to advancing contemporary art in Maine through direct engagement with artists and the public, creating exceptional exhibitions and education programs that communicate the transformative power of the art of our time. CMCA’s Education department partners with Rock City Cafe to exhibit works that support the next generation of contemporaries.